Fatigue and Alertness – Adjusting to the Pace of Space

Astronaut’s sleep is disrupted by a variety of sources, such as sleep shifting due to visiting vehicle docking operations, 90 minute days with a sunrise and sunset every 45 minutes, nighttime alarms, and more. Yet, with all of those challenges, the astronauts still must be alert and able to reliably and safely perform their jobs.

According to Dr. Smith Johnston, M.D., a NASA flight surgeon at Johnson Space Center (JSC) and Lead of the Fatigue Management Team, they currently monitor the astronauts by closely observing and talking with them in an effort to make a subjective determination about the astronauts’ fatigue state.

“We follow their dynamic schedule through daily tag ups, other regularly scheduled meetings as well as weekly private medical meetings, all in effort to make a subjective determination. We also track their sleep patterns using actigraphy.”

Knowing that each astronaut is different and realizing that they needed to be able to quantify and measure fatigue more objectively, NASA relied on the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program’s solicitation to find solutions.

“The SBIR proposals allowed us to look at many different monitoring tools and technologies from a number of small businesses that have the strengths to support what’s needed,” says Kristine Kennedy Ohnesorge, Sleep/Fatigue Research Portfolio Manager, NASA’s Human Research Program/Behavioral Health and Performance (BHP) Element within its Biomedical Research and Environmental Sciences Division at JSC.

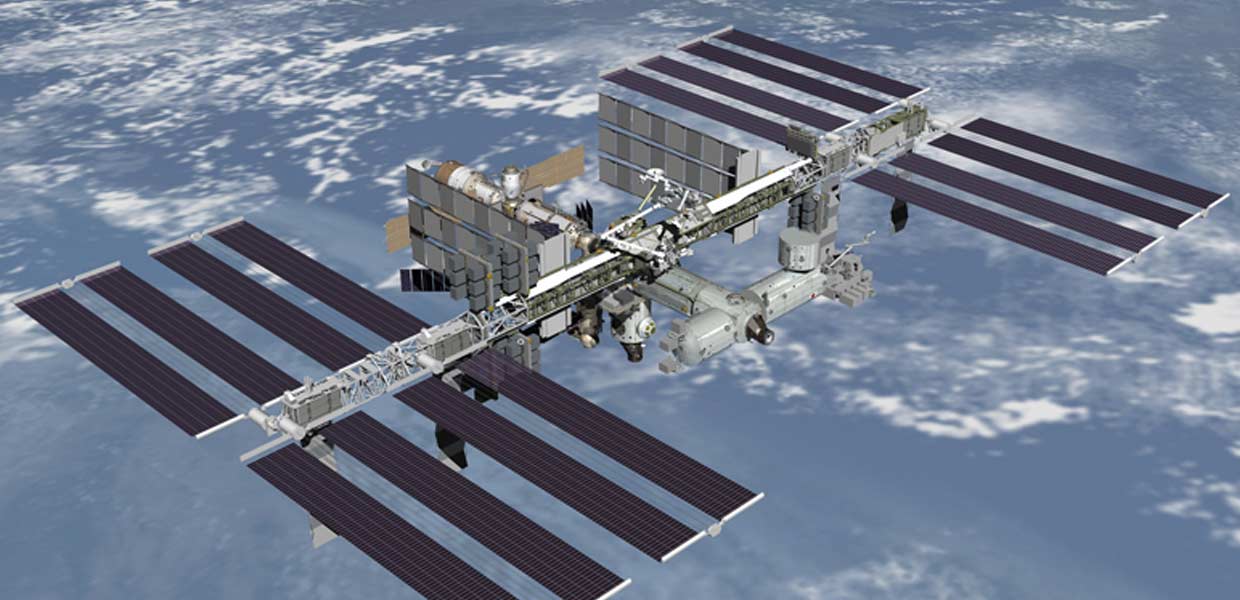

At the time, Daniel Mollicone, PhD, Chief Executive Officer of Pulsar Informatics, Inc., in Philadelphia, was working with a world-renowned sleep expert on a project for astronauts on board the ISS.

“We were collaborating with Dr. David Dinges, the PI, to develop a software version of a psychomotor vigilance test for the astronauts. We saw the NASA need very clearly—to quantify and measure fatigue. But, there a gap as to how the data would get to the end-user and what it would mean to them.”

The BHP group at JSC awarded Pulsar the first of several SBIR contracts to help develop a way to collect and integrate astronaut data in the context of factors that could be impacting their behavioral health and performance.

“One thing that makes Pulsar stand out as a small business is they not only have the expertise to develop the product but they also understand the science.”

Kristine Kennedy Ohnesorge, Sleep/Fatigue Research Portfolio Manager

Kristine says, “One thing that makes Pulsar stand out as a small business is they not only have the expertise to develop the product but they also understand the science.”

Sandra Alexandra Whitmire, PhD, Sleep/Fatigue Research Portfolio Scientist and Deputy Element Scientist for BHP, agrees.

“They have an appreciation for the challenges of the spaceflight environment and proposed above and beyond, outlining how they would enhance our request for a tracking system by providing a tool that could enable informed recommendations for the timing and implementation of countermeasures”

Through the funding from their first three SBIR awards, Pulsar built a platform technology that was very powerful.

According to Daniel, “First, we addressed fatigue. Then, we extended the platform to address what happens if an astronaut has a behavioral health problem that could jeopardize mission objectives. So, we adapted the system to integrate markers heightened chronic stress, such as from the heart, cortisone, etc.”

Data related to factors, such as fatigue, alertness, sleep history, performance, are collected from the astronauts and sent to their software on a server.

“The software synthesizes the data and forecasts future health and performance outcomes based on biomathematical models. A flight surgeon can then look at ‘what if’ scenarios and identify the best countermeasures. We can figure out when they might nap, eat, or perform a task to maximize their schedule,” says Smith.

“We can say ‘no more,’ or cancel an experiment to give them time to rest, time to take a day off, or to possibly take medication.”

Sandra says, “The Pulsar tool is not operational yet on ISS, as NASA still has to get data to feed the system, as well as implement the Dashboard with users working missions– such processes will take a while”.”

In the future, the intent is for the technology to play a role in monitoring astronauts who have to adjust to living and working in space.

“The SBIR program is a great vehicle for finding technical solutions, and Pulsar is an example of being able to bridge the gap and fill the need,” states Kristine.

Through an SBIR Phase I, Pulsar has been developing a sleep and activity monitor that an astronaut could wear. Called “STARwatch,” the device would collect the data and autolink to a server on the ground.”

For Dr. Daniel Mollicone, working on these technologies and providing the solutions for NASA’s needs has been exciting.

Space exploration leads to new engineering challenges to solve. Essentially, “NASA invents cool problems with their imagination. That’s oxygen for an engineer. They should be called, ‘The Department of Imaging New Problems to Solve.’ It’s really a compliment.” In solving these engineering challenges we gain insight about ourselves and develop new technologies that contribute to economic growth and make life better here on Earth.